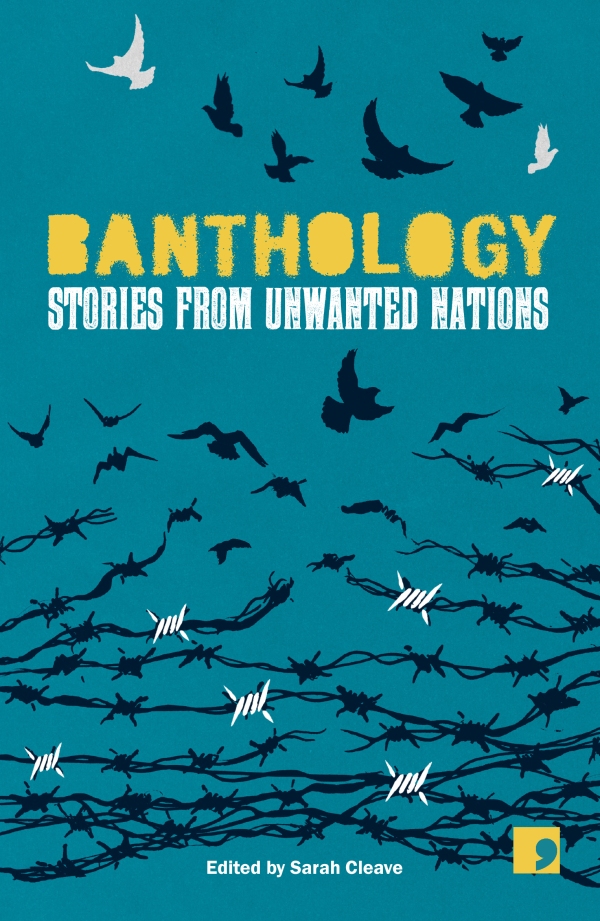

Banthology: Stories from Unwanted Nations, edited by Sarah Cleave. Comma Press, Manchester, UK: 2018

Seven contributors – academics, activists, artists and writers from the Middle East, of various generations – were specially commissioned by Comma Press to write in response to President Trump’s Executive Order 13769. This was the January 2017 order that became known to those protesting against it as the ‘Muslim ban’.

People from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Yemen, Somalia and Sudan were not allowed to enter the United States for 90 days. In addition, refugee resettlement was halted for 120 days and Syrian refugees banned indefinitely.

The contributors:

- Wajdi al-Ahdal

- Rania Mamoun

- Anoud

- Fereshteh Molavi

- Najwa Binshatwan

- Zaher Omareen

- Ubah Cristina Ali Farah

The January 2018 release of this book synchronises with the initial implementation of the travel ban (it has undergone various changes since). The editor’s rationale for Banthology: Stories from Unwanted Nations was to ‘champion, give voice to, and better understand a set of nations that the White House would like us to believe are populated entirely by terrorists.’ The writers were asked to respond with fictional pieces ‘exploring themes of exile, travel and restrictions on movement.’

The idea was to represent a range of experiences, not only from those living inside ‘banned’ nations but also those living in exile. Among these latter are Anoud, who moved from Iraq to New York just before the first travel ban and was ‘scared to leave in case she wasn’t allowed to return.’ Here, the account of Anoud’s Storyteller, Jamela, is framed by the scene of her sitting eating a meal in an Indian takeaway in east London. In between, she tallys up her ‘firsts.’ ‘In 1996, I felt hunger for the first time in my life…’, ‘In 2003 I took shelter in my first bunker…’: she tumbles into a freefall of loss, bereavement and homelessness.

Wajdi al-Ahdal has experienced exile on different terms. A Yemeni novelist, screenwriter and dramatist as well as a short story writer, he was accused of insulting ‘morality, religion, and conventions of Yemeni society’ for his novel Mountain Boats. The book was confiscated by the Yemeni Ministry of Culture and al-Ahdal was obliged to live in exile for a time due to the campaign against it.

Each one of these stories challenges stereotypes of Arabic people in the West and engages in some way with themes of freedom of movement, freedom of speech and the migrant experience. Zahar Omareen, who presents here the wry, ironic The Beginner’s Guide to Smuggling, is a Syrian writer and researcher based in London, who has co-curated exhibitions on the art of the Syrian uprising. His story tells of a man’s journey from Syria to France and then on to Sweden, never without a sense of humour and of the absurd.

Rania Mamoun’s Bird of Paradise begins and ends in an airport. A story of regret and defeat, the protagonist recalls wishing, as a child, that she had been born a bird of paradise. She moves onto consider the first time she left her city on a trip to a nearby village and the beating she received from her brother Ahmad for leaving home without permission. She was later thwarted again by Ahmad who refused to let her study at the University of Khartoum. She went to the less prestigious Gezira University instead and ‘made very slow progress.’

She finally decides to make a break for it; her cousin Ashwaq comes to the airport to see her off; everything is arranged. But when the time comes to board the plane ‘a mysterious force, some hidden obstacle, brought me to a standstill.’ It was not, as it were, a travel ban. Mamoun refuses to pay Trump’s divisive edict the complement of a mention. Instead, the protagonist looks in the mirror in the airport toilets with a poignant sense of resignation. ‘I have grown older, and somehow outgrown the desire I once felt.’

In Phantom Limb, Fereshteh Molavi’s protagonist writes a blog with each entry subheaded ‘On a Monday,’ ‘On a Tuesday.’ Like Mamoun’s story, and Anoud’s, it almost ends back at the beginning. ‘I’d woken up with an old idea that turned into a sudden decision. I would start blogging again,’ becomes ‘I’d woken up with an old idea that turned into a sudden decision. I’d stop blogging in order to let my phantom roommates free me of my writer’s block.’ In between, the protagonist and his roommates, Syrian-Armenian Varuzh, Iranian Kurd Farhad and Najib, who had ‘fled from the Taliban’, spend their days working at ‘the same miserable factory, making cabinets.’ The protagonist met them online and ‘soon realised that they would do anything to be on the stage.’ He himself has a dream of becoming a successful theatre director.

The story revolves around preparations for an after-dinner performance at their apartment in Toronto, while at the same time Farhad acquires phantom limb syndrome when his mother’s leg is cut off back home. It’s a beautiful, mournful story vividly bringing to life each of the characters, from the roommates to the factory boss, ‘Bottomless Gut’, who is constantly devouring piles of food and recounting his ‘journey from lowly immigrant to top-class businessman’, to the girl in solitary confinement about to be executed, who is remembered only by the sound of her voice humming an old folk tune.

Return Ticket by Najwa Binshatwan of Libya is the story of a woman of the fictional, allegorical village of Schrödinger – a ‘cosmic anomaly… it could move through time and space, changing its orbit spontaneously, as if it were the sun rising in one place and setting in another.’ The woman, addressing her grandson, asks that he respects the ‘graves of the six American tourists that visited the village and never left it.’ These Americans have a speaking part, with occasional telling statements such as: ‘it’s good that we died before America’s prison warden came to power.’

Schrödinger is imbued with a volition of its own – the will of the people; it hovers over America ‘twice a week, hoping to return the bodies of the six American tourists.’ The grandmother only leaves Schrödinger once to visit her husband. When she finally reaches him he flies into a rage and divorces her due to her lack of hijab and underwear. After years stranded at the airport, like the woman in Bird of Paradise, she finally buys a return ticket home.

Jujube by Ubah Cristina Ali Farah from Somalia is a heartbreaking, magical tale of loss told through the eyes of the young asylum seeker Ayan Nur and rendered in gorgeous imagery. Ayan remembers her mother’s house, built with ‘flamboyant tree branches and braids of palms… At dawn, the walls are streaked with coral iridescence like in a sea cave’; when war breaks out ‘the city burns and glows like a brazier, a filthy firework under the full moon’; the dog at the villa where Ayan takes a job as a nanny has eyes ‘the colour of bananas’.

Four brief ‘Interpreter’s notes’ punctuate transitions from the present to the remembered recent past: ‘numerous are the omissions and incongruences of the events described in the course of the hearing for a request for asylum…’ The final note ends the piece with a feeling of immense desolation. The story is however filled with subtle counterpoints. While Ayan Nur’s mother is a herbalist, ‘her face yellow with turmeric and butter, the precious ingredients of her beauty mask… she makes a decoction of roots to protect us from typhus and cholera, pneumonia and measles…’, the mistress of the villa doesn’t understand the tradition of care that Ayan lavishes on her two-year-old daughter’s hair, and as she walks, she dirties her clothes ‘with the rich soil and the orange pollen from the lilies… she has no other reason to garden, no purpose other than beauty.’ Meanwhile the little daughter picks dry hydrangea petals and crushes them into dust – a childlike action with an inert, ineffectual result.

Wajdi al-Ahdal’s piece The Slow Man, is the final story of Banthology. With its massive timespan, mapped out in Babylonian epochs, it serves to remind us of the way humans mark out global futures through their actions, which while they take place in the present, can generate irrevocable change, not always for the better.